Why Rydberg Atoms Matter Right Now

Rydberg atoms are ordinary neutral atoms—rubidium, cesium, and friends—promoted to states of very high principal quantum number nnn. Their valence electron orbits far from the nucleus, ballooning the atom’s size by n2n^2n2 and supercharging properties that are otherwise tiny: polarizability scales roughly as n7n^7n7, dipole matrix elements as n2n^2n2, interaction strengths as high powers of nnn. In practice, that means two atoms separated by several micrometers—distances you can resolve and address optically—can interact strongly and quickly. This is the rare sweet spot in quantum engineering where large distances and strong interactions coincide, making Rydberg atoms a natural foundation for fast, native two-qubit gates in programmable arrays of optical tweezers.

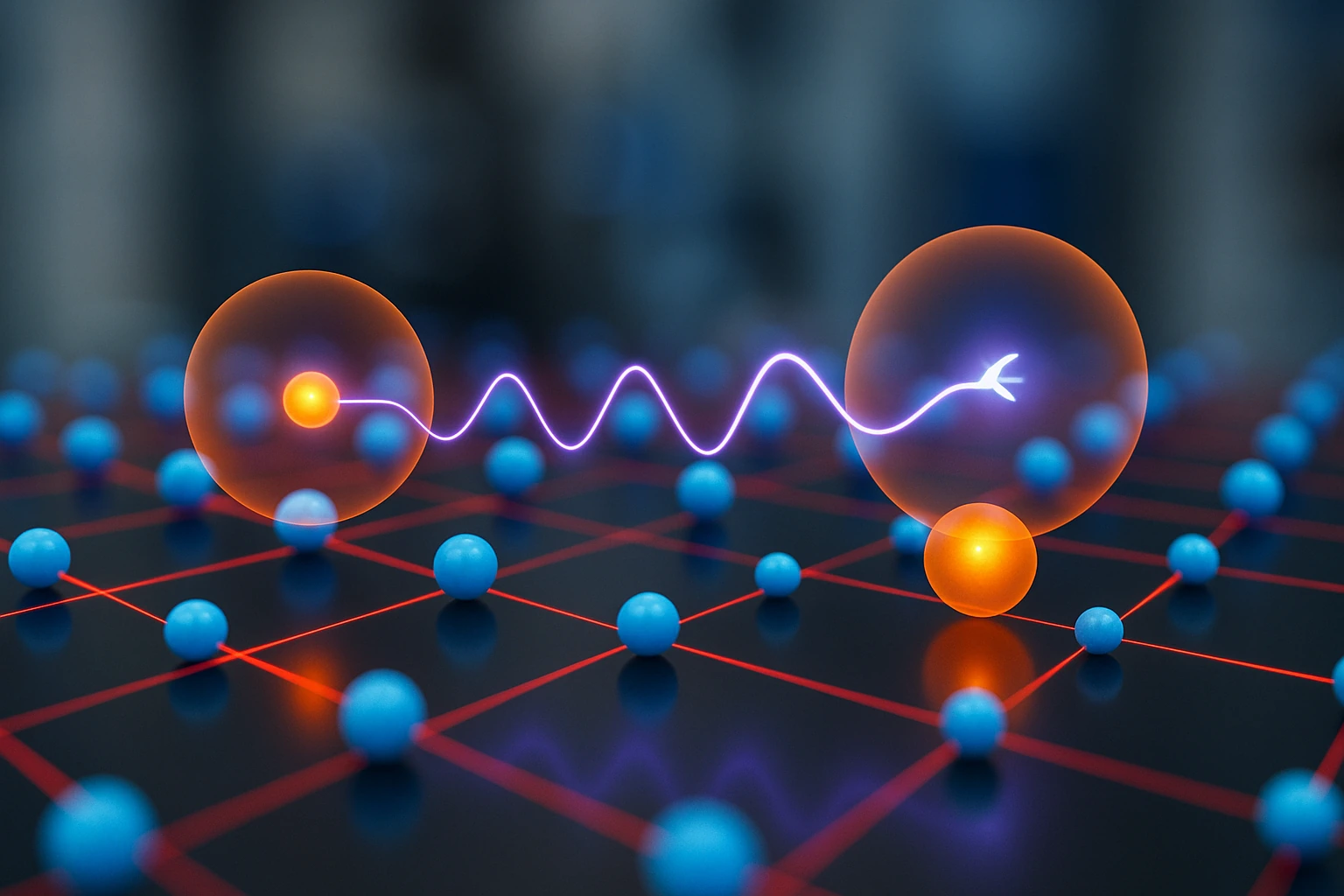

The Blockade Idea in One Picture

Imagine two atoms A and B, each a qubit stored in a pair of long-lived ground hyperfine states ∣0⟩|0\rangle∣0⟩ and ∣1⟩|1\rangle∣1⟩. A laser couples ∣1⟩|1\rangle∣1⟩ to a high-lying Rydberg state ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩ with Rabi frequency Ω\OmegaΩ. If A is excited to ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩, the energy of the state ∣rr⟩|r r\rangle∣rr⟩ for the pair shifts by a large interaction V(R)V(R)V(R) that depends on their separation RRR. When V≫ΩV \gg \OmegaV≫Ω, the laser is far off-resonant for exciting B to ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩ while A is already there. B’s excitation is “blockaded.” That is the Rydberg blockade: one atom in ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩ prevents its neighbors from following, enforcing an effective two-level dynamic across multiple particles and turning a many-body problem into a controlled, collective one.

Two regimes set the microscopic origin of V(R)V(R)V(R). In the

van der Waals regime (no resonant energy exchange between atoms), V(R)∼C6/R6V(R)\sim C_6/R^6V(R)∼C6/R6. Near a

Förster resonance, where pair states nearly match in energy and exchange dipole-dipole interactions turn on, the coupling becomes ∼C3/R3\sim C_3/R^3∼C3/R3, dramatically increasing the blockade range. By choosing nnn, atomic species, and a small dc electric field, experimentalists tune between these regimes and set the

blockade radius RbR_bRb, defined by V(Rb)=ℏΩV(R_b)=\hbar\OmegaV(Rb)=ℏΩ. Inside RbR_bRb, only one Rydberg excitation is allowed at a time; outside RbR_bRb, atoms behave independently.

Collective Rabi Physics and Its Use

With several atoms inside one blockade sphere, they act like a single “superatom”: the laser couples the symmetric ground state to a singly excited Dicke state with an

enhanced Rabi frequency Ωcoll=N Ω\Omega_{\text{coll}}=\sqrt{N}\,\OmegaΩcoll=NΩ. This collective N\sqrt{N}N speedup is useful for fast operations such as deterministic single-photon sources and entanglement preparation; in the gate setting, it is mostly a design detail you must either leverage or suppress depending on geometry. For two-qubit gates in tweezer arrays, we typically keep just one atom per site inside mutual blockade so Ωcoll\Omega_{\text{coll}}Ωcoll reduces to Ω\OmegaΩ, simplifying calibration.

From Blockade to Entangling Gates

The most common entangling primitive is a controlled-phase (CZ) gate built with three pulses:

- π-pulse on the control: If the control is ∣1⟩|1\rangle∣1⟩, it goes to ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩; if it is ∣0⟩|0\rangle∣0⟩, nothing happens.

- 2π-pulse on the target: Attempt to drive ∣1⟩↔∣r⟩|1\rangle\leftrightarrow|r\rangle∣1⟩↔∣r⟩ on the target. If the control sits in ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩, blockade detunes the target and the 2π does not complete; if the control is in a ground state, the target executes a clean 2π and accumulates a phase.

- π-pulse to de-excite the control: ∣r⟩→∣1⟩|r\rangle\rightarrow|1\rangle∣r⟩→∣1⟩, closing the interferometer on the control.

After trivial single-qubit frame updates, this sequence implements CZ with duration T∼4π/ΩT\sim 4\pi/\OmegaT∼4π/Ω, often tens of nanoseconds to a few hundred nanoseconds—significantly faster than many other neutral-atom two-qubit gates. A CNOT follows by wrapping CZ with Hadamards on the target. Alternative

phase-modulated and

adiabatic protocols smooth sensitivity to laser noise and finite blockade, and

Rydberg dressing—off-resonant coupling to ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩—creates softer, longer-range interactions for analog simulation and multi-qubit phase gadgets, at the cost of slower rates.

The Hardware Stack That Makes It Work

A modern neutral-atom processor starts with a 2D (sometimes 3D) array of optical tweezers at 700–1000 nm. A magneto-optical trap loads atoms stochastically;

rearrangement with steerable beams or acousto-optic deflectors shuffles them into defect-free patterns. Two laser systems define the qubit and the gate: one pair (often Raman or microwaves) for ground-state single-qubit rotations, and one high-power, narrow-line laser (or two-photon ladder) for Rydberg excitation. Typical separations are 3–6 µm, setting the mutual blockade at n∼60n\sim60n∼60–110. Site-selective addressing comes from tightly focused beams or frequency multiplexing; global beams provide uniform illumination for the target 2π steps. Stabilized phases and intensities, active pointing control, and low phase noise are non-negotiable: the physics offers fast gates, but only if the optical engineering keeps the Rabi area and detuning where the Hamiltonian says they are.

Error Sources and What They Teach You to Optimize

Rydberg gates fail gracefully: each imperfection points to a clear knob.

- Finite blockade (leakage): If V/ΩV/\OmegaV/Ω is not large, the target partially excites during the blocked 2π, leaving residual population and phase errors. You can increase nnn, move atoms closer, use Förster tuning, or reduce Ω\OmegaΩ (trading speed for fidelity) to raise V/ΩV/\OmegaV/Ω.

- Rydberg decay and blackbody transitions: The Rydberg lifetime scales as n3n^3n3 in vacuum and is limited by blackbody-induced jumps. Gate time ∝1/Ω\propto 1/\Omega∝1/Ω must be short compared to lifetime; cryogenic environments or carefully chosen nnn mitigate this.

- Doppler and motion: Although atoms are cooled, residual motion Doppler-shifts the excitation, especially for two-photon ladders with nonzero wavevector. Counter-propagating beams reduce sensitivity; magic trapping that equalizes polarizability of ground and Rydberg states can keep atoms confined during gates to avoid motional dephasing.

- Laser noise: Intensity and phase noise map directly to Rabi area and detuning errors. Narrow-line lasers with high servo bandwidth and stable fiber delivery are essential; composite pulses and adiabatic sweeps add robustness.

- Crosstalk: Addressing beams spill light onto neighbors; shelving qubits in ∣0⟩|0\rangle∣0⟩, staggering pulse timing, or using local Stark shifts to detune spectators suppresses unintended rotations. Geometry helps: larger spacings reduce spill but weaken blockade, so arrays often adopt interleaved activation patterns.

Gate infidelity budgets typically break into a few tenths of a percent from each of these mechanisms in state-of-the-art systems, with the product setting overall two-qubit error. Because the primitives are short, slow drifts are less harmful than fast noise; most engineering effort chases sub-kilohertz linewidths and percent-level power stability at microsecond timescales.

Scaling: Arrays, Connectivity, and Compilation

Blockade is local (micrometer scale), but tweezer arrays are reconfigurable.

Atom transport—moving tweezers during idle periods—creates effective long-range connectivity. Some platforms implement

shuttling architectures where atoms rendezvous for gates and return. Others rely on

multitone addressing and

simultaneous parallel gates on disjoint pairs, exploiting the fact that blockade spheres do not

overlap if you choose a checkerboard pattern. Compilers map circuits into these constraints, inserting swaps only when necessary and scheduling to minimize simultaneous crosstalk. The sweet spot today balances density (for fast, strong blockade) against optical access (for many beams and sensors). Modular stacks—several subarrays linked optically—are emerging to extend qubit counts without sacrificing per-site control.

Why Blockade Feels Native for Digital Quantum Logic

Some qubit technologies must synthesize entanglement from weak, indirect couplings; Rydberg blockade delivers a

direct conditional dynamic with the analog of an if-statement baked into the Hamiltonian: “if control is in ∣1⟩|1\rangle∣1⟩, target rotations are off.” That conditionality mirrors the structure of controlled-phase gates, so the mapping from physics to logic is short and efficient. Moreover, the

energy scale of Rydberg interactions (tens to hundreds of MHz at a few micrometers) is large compared with typical decoherence rates, enabling nanosecond–microsecond gates that outpace many noise channels. Add in the ability to

rearrange qubits and to

address individually with diffraction-limited optics, and you get a platform where layout, scheduling, and calibration become classical engineering problems rather than fundamental roadblocks.

Practical Design Heuristics Before You Start

Pick an nnn and spacing that give V/Ω≳10V/\Omega \gtrsim 10V/Ω≳10 for comfort; design for Ω/2π∼1\Omega/2\pi\sim 1Ω/2π∼1–5 MHz so π-pulses are 100–500 ns; keep Doppler broadening below a few hundred kHz with sub-10 µK atoms and nearly counter-propagating beams; add electric-field control with stable compensation to tame stray dc fields that Stark-shift ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩. Verify blockade with a

pair scan: measure the target’s Rabi oscillations with and without the control in ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩ as a function of distance. Build a

calibration tree in software that from time to time remeasures Rabi areas, light shifts, and local detunings per site. Finally, architect experiments so single-qubit rotations are cheap and precise; they carry most of the burden of echoing away slow errors and compiling CZ into the gate your algorithm expects.

Where This Leads Next

Blockade has already enabled Bell states across thousands of pairs, GHZ strings, surface-code primitives in prototype patches, and programmable analog simulators dressed off-resonantly. The frontier now is

error-corrected two-qubit gates that hold up under repeated use inside small codes,

magic trapping that neutralizes differential shifts to allow gates inside static traps,

cryogenic arrays to extend Rydberg lifetimes, and

pulse engineering that flattens sensitivity to finite blockade without giving up speed.

Pulse Engineering: From Square Bursts to Robust Sequences

The textbook blockade CZ uses square π–2π–π pulses. They are fast and simple, but small detuning or amplitude errors bend the Rabi area and leave residual population in ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩ or spurious phases on ∣1⟩|1\rangle∣1⟩. Two families of remedies dominate.

Composite pulses (BB1, CORPSE, SCROFULOUS-style variants adapted to Rydberg ladders) stitch together rotations with chosen phases so that first- and even second-order amplitude errors cancel. In practice, a target 2π can become a sequence like {πϕ1, 2πϕ2, πϕ1}\{\pi_{\phi_1},\ 2\pi_{\phi_2},\ \pi_{\phi_1}\}{πϕ1, 2πϕ2, πϕ1} with phases ϕ1,2\phi_{1,2}ϕ1,2 picked to flatten sensitivity to Ω\OmegaΩ miscalibration. The control’s π pulses receive shorter, phase-symmetric composites so time overhead stays modest. The other family is

adiabatic: chirp the detuning and amplitude so the system follows an instantaneous eigenstate and returns with a geometric phase that is conditional on blockade. Rapid-adiabatic-passage (RAP) and STIRAP-like ladders (for two-photon excitation) tolerate detuning drifts and inhomogeneous light shifts at the cost of longer gate times and careful limits on nonadiabatic leakage. Many groups now blend the two—adiabatic envelopes carrying embedded phase flips—because Rydberg errors are dominated by fast noise and finite blockade, not slow thermal drift.

Förster Tuning and the Art of Making VVV Big

Blockade thrives when V/ΩV/\OmegaV/Ω is large. You can’t always move atoms closer or push nnn higher without inviting crosstalk and blackbody decay. The elegant lever is

Förster resonance: choose a pair of Rydberg states whose two-atom energies nearly match a different product pair ∣rr⟩↔∣r′r′′⟩|r r\rangle \leftrightarrow |r’ r”\rangle∣rr⟩↔∣r′r′′⟩. A small dc electric field Stark-shifts levels into resonance, turning the interaction from van der Waals (∝R−6\propto R^{-6}∝R−6) into resonant dipole-dipole (∝R−3\propto R^{-3}∝R−3), increasing RbR_bRb dramatically. Practically, you pre-calibrate a “Förster map”: interaction strength versus field for your chosen nnn and polarization. During gates, a stable compensation system (guard electrodes, low-noise supplies, active feedback from Rydberg spectroscopy) pins the field where VVV is maximal and the derivative dV/dEdV/dEdV/dE is small, so ambient fluctuations do not modulate the phase. This tuning also lets you

park the system off-resonance during idle periods to reduce unintended dressing, then step onto resonance only for the gate.

Dressing, Echoes, and Multi-Qubit Phases

Resonant blockade is not the only route.

Rydberg dressing couples ∣1⟩|1\rangle∣1⟩ weakly to ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩ with detuning Δ\DeltaΔ, producing an effective two-body phase ∝Ω4/(Δ3)\propto \Omega^4/(\Delta^3)∝Ω4/(Δ3) that is longer-range and softer than hard blockade. Dressing gates implement controlled-phase by idling under this interaction for a calibrated time, wrapped in

spin echoes to cancel single-particle light shifts. They tolerate finite spacing variations and enable

parallel multi-qubit phase gadgets useful in variational algorithms and analog simulation. The trade is speed and sensitivity to technical noise over longer windows; still, when combined with local Stark shifts that detune spectators, dressing becomes a versatile tool for entangling patterns beyond nearest neighbors without shuttling.

Magic Trapping and Motion-Proof Gates

Exciting to ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩ changes the polarizability, so atoms feel a different trap; turning traps off avoids dephasing but lets atoms wander and heat on re-capture. The emerging solution is

magic trapping: engineer wavelengths and polarizations so the ground and Rydberg states see the same (or near-equal) ac Stark shift. In tweezers, this uses a small electric field and polarization control to balance scalar and tensor components. With magic conditions, you keep traps on, hold temperature, and cut Doppler and line-pulling. Even when exact magic is elusive,

micromotion compensation (counter-propagating beams, Raman sideband cooling, tight alignment) and

phase cycling (echo sequences across motional states) suppress motion-induced errors to the sub-10−3^{-3}−3 level at MHz Rabi rates. The headline is stability: once motional sensitivity is tamed, composite or adiabatic gates become predictably repeatable day to day.

Error Budgets You Can Act On

A transparent error budget guides engineering. Decompose entangling infidelity 1−F1-\mathcal{F}1−F into:

blockade leakage (ϵblk∼(Ω/V)2\epsilon_{\text{blk}}\sim (\Omega/V)^2ϵblk∼(Ω/V)2),

Rydberg decay (ϵγ∼T/τr\epsilon_{\gamma}\sim T/\tau_rϵγ∼T/τr),

Doppler/inhomogeneous detuning (ϵΔ∼(δ/Ω)2\epsilon_{\Delta}\sim (\delta/\Omega)^2ϵΔ∼(δ/Ω)2 after mitigation),

laser amplitude/phase noise (ϵΩ,ϵϕ\epsilon_{\Omega},\epsilon_{\phi}ϵΩ,ϵϕ), and

crosstalk (ϵxt\epsilon_{\text{xt}}ϵxt). Assign targets—e.g., ϵblk≤2×10−3\epsilon_{\text{blk}}\le 2\times10^{-3}ϵblk≤2×10−3, ϵγ≤5×10−4\epsilon_{\gamma}\le 5\times10^{-4}ϵγ≤5×10−4, ϵΔ≤5×10−4\epsilon_{\Delta}\le 5\times10^{-4}ϵΔ≤5×10−4, ϵΩ+ϵϕ≤10−3\epsilon_{\Omega}+\epsilon_{\phi}\le 10^{-3}ϵΩ+ϵϕ≤10−3, ϵxt≤5×10−4\epsilon_{\text{xt}}\le 5\times10^{-4}ϵxt≤5×10−4—and back-solve for design: set V/Ω≥15V/\Omega\ge 15V/Ω≥15, Ω/2π≈2\Omega/2\pi\approx 2Ω/2π≈2–4 MHz, nnn and temperature for τr≳100\tau_r\gtrsim 100τr≳100 µs (cryogenic if needed), and laser servo bandwidth ≳1\gtrsim 1≳1 MHz with short-term relative intensity noise below 10−3/Hz10^{-3}/\sqrt{\text{Hz}}10−3/Hz at 10–100 kHz. Build dashboards that log these proxies—Rabi area stability, Ramsey linewidths, blockaded Rabi suppression—so drifts are caught before they tax fidelity.

Calibration Routines That Scale

As arrays grow, hand-tuning fails. A scalable routine looks like this: (1)

Global coarse—measure and set the global Rabi frequency and detuning with a small set of “sentinel” sites across the array. (2)

Per-site light-shift trims—apply weak local Stark tones to null residual detunings extracted from short Ramsey probes; store trims in a map. (3)

Blockade verification—on a sparse grid of pairs at representative separations, compare target Rabi oscillations with/without the control in ∣r⟩|r\rangle∣r⟩; fit V(R)V(R)V(R) and update the compiler’s spacing constraints. (4)

Automated phase scans—run the full CZ sequence while sweeping a single-qubit phase on the target; the interference fringe gives the conditional phase and population leakage. (5)

Composite/adiabatic knob sweep—periodically re-optimize phases or chirp rates using Bayesian or Nelder–Mead searches seeded by previous values. These steps run nightly; quick sentry measurements run hourly and gate the start of long jobs. The software outcome is a

calibration tree tied to hardware state (laser locks, electrode voltages, tweezer powers) so a warm start lands you back inside the fidelity window.

Benchmarking Beyond Bell States

Bell-state contrast is necessary, not sufficient. Use

interleaved randomized benchmarking (iRB) for two-qubit gates to extract average error under realistic spam; complement with

cycle benchmarking to separate coherent from stochastic components. Add

cross-entropy or

process purity measures if your application is analog-like. For scaling studies, run

XEB-like circuits on checkerboard tilings to stress parallelism without overlapping blockade spheres; compare error versus gate density to quantify crosstalk. In error-correcting contexts, prefer

logical-state lifetimes and

stabilizer parity success as system-level metrics; they tease out whether residual coherent errors align destructively or constructively with the code’s symmetries. All of this folds back into pulse choices: if coherent error dominates, tilt toward composite sequences; if stochastic drift dominates, adiabatic ramps and echo padding buy more.

Layout, Scheduling, and the Compiler’s Hand

Because blockade is local,

layout determines compilation cost. A good compiler colors the interaction graph into independent edge sets (e.g., a checkerboard of disjoint pairs), schedules gates in two to four layers, and inserts

park detunings or light-shift shields for spectators. If long-range entanglement is needed, it inserts

shuttles: move atoms along conveyor tweezers while global operations run elsewhere. Motion overlaps with idle periods to hide latency.

Frequency multiplexing—several addressing tones sent through a multi-channel AOD—lets you address many pairs at once with low crosstalk; the compiler ensures spectral spacing avoids beat-note hazards. Ultimately, software awareness of RbR_bRb, V(R)V(R)V(R), and per-site trims converts a physics device into a deterministic logic engine where gate counts, durations, and conflicts are predictable inputs to algorithmic planning.

Cryogenic Operation: When and Why

At room temperature, blackbody radiation shortens Rydberg lifetimes and induces state hops that randomize phases. Cooling the environment to 4–77 K can multiply τr\tau_rτr and stabilize energy levels, relaxing pressure on speed and allowing slightly higher nnn without penalty. The engineering bill includes cold-compatible optics, reduced outgassing, and managing contraction in electrode stacks used for field control. Magic trapping is easier at cryo because stray charge dynamics slow down; compensation voltages remain stable for hours. Cryo is not mandatory for useful gates, but it widens margins and simplifies the error budget—particularly attractive for error-correction experiments where repeated two-qubit gates amplify rare decay events.

Putting It Together: A Practical Gate Recipe

A concrete, high-fidelity CZ might look like this. Choose n=70n=70n=70 in rubidium, spacing R=5R=5R=5 µm, Förster-tuned to resonant dipole-dipole so V/2π∼50V/2\pi \sim 50V/2π∼50 MHz. Set Ω/2π=3\Omega/2\pi=3Ω/2π=3 MHz on both control and target. Keep traps on under quasi-magic conditions with residual differential shift <100<100<100 kHz. Run a composite control π\piπ of three subpulses totaling 120 ns; apply an adiabatic 2π on the target with a Blackman envelope and a ±2\pm 2±2 MHz chirp over 300 ns; de-excite control with the time-reversed composite π\piπ. Surround with single-qubit echo rotations to cancel static light shifts. Total entangling time ~600–700 ns. Measured leakage <3×10−3<3\times10^{-3}<3×10−3, decay contribution <7×10−4<7\times10^{-4}<7×10−4, Doppler <5×10−4<5\times10^{-4}<5×10−4, residual coherent phase error corrected in software by a frame update. Parallelize across a checkerboard so half the array entangles per layer; two layers complete a full nearest-neighbor round.

Outlook: From Physics Tricks to Reliable Logic

The trajectory is clear. Better

electrode stability and

Förster control will make VVV a software knob; broader

magic windows and

cryogenic operation will flatten motional and lifetime constraints; smarter

pulse compilers will pick among square, composite, and adiabatic shapes based on live calibrations; and array-level

transport will provide effective all-to-all connectivity without abandoning micrometer-scale strength. The core advantage remains unchanged: blockade implements a conditional dynamic that maps cleanly to digital entangling gates at nanosecond–microsecond timescales. With disciplined calibration, robust pulse design, and compiler-aware layouts, the “giant atom” becomes a reliable transistor of the quantum world—fast, conditional, and local—ready to be tiled, scheduled, and corrected into the scalable computation that a few years ago felt like a thought experiment and now looks like an engineering plan.